Article written by: Amanda Hunter & Tracey P. Lauriault

Introduction

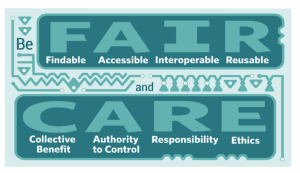

Since early June, the Tracing COVID-19 Data project team has been examining intersectional approaches to the collection, interpretation, and reuse of COVID-19 data. Our most recent post about Open Science innovation during the pandemic highlighted the critical role Open Science (OS) plays in the rapid response to COVID-19, ensuring that data and research outputs are more widely shared, accessible, and reusable for all. That post also chronicled the importance of the principles and standards that support OS such as FAIR principles, open-by-default, and the open data charter. We also emphasized the significance of Indigenous data sovereignty and the value of integrating CARE and OCAP principles into data management and governance.

As a continuation; this post analyzes Canada’s ongoing commitment to adopting OS standards and principles. Canada has a government directive for implementing open science as stated in Canada’s 2018-2020 National Action Plan on Open Government, Roadmap for Open Science, Directive on Open Government, and the Model Policy on Scientific Integrity. These are commitments and guidelines for the adoption of open science standards and part of open data and open government at the federal level.

Here we assess whether or not official provincial, territorial and federal public health reporting adheres to open science & open data standards when reporting of the COVID-19 data. We will address the following questions:

- Are COVID-19 data open in Canada?

- Under what licenses are COVID-19 data made available?

- Are there active open data initiatives at all levels of government? And are they publishing COVID-19 Data? (Federal, Provincial, Territorial)

We draw conclusions from our observations of the current state of open data in Canada, particularly as it relates to COVID-19 data. We will identify areas of opportunity and make concrete recommendations to facilitate open data and open science during pandemic. It should be noted that we are citing federal mandates: though provincial and territorial governments that do not have open data and open government mandates are not obliged to adhere to Federal open data/open government directives, although we would argue that it would be largely beneficial if these levels of government considered adopting an open data framework, similar to directives aimed at the federal level, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. Some jurisdictions have their own frameworks and we will discuss those as well.

Methodology

To support this analysis we have developed a framework which incorporates FAIR principles, OCAP principles, CARE principles, and the open data charter. Using this framework, we will assess Canada’s reporting process to determine which standards are being used and which – if any – should be considered.

To collect data we visited Canada’s official COVID-19 reporting sites (found here) and used the walkthrough method to assess existing data dissemination practices. We located license information for each webpage/dashboard and recorded this information, as well as supplementary information including disclaimers, terms of use, and copyright information (see the observations here). Importantly, we made note of which province/territory has open data/open government portals, checking to see if the COVID-19 data were made available via these portals. This approach informed the determination of the following:

- Whether or not the information were open

- The License under which the data are available (which determines how one is allowed to access/reuse the data)

- Whether or not the respective province or territory has an open data mandate

- Whether or not the respective province or territory has an open data portal

For the purposes of this blog post we focused on the license under which the COVID-19 data are disseminated, whether or not there is a copyright statement, and, whether or not the data are open. Future posts will assess other aspects of Canada’s official reporting sites using this same framework.

The Framework

There are a number of key standards which inform our assessment.

Open Science

Open Science (OS) is a movement, practice and policy toward transparent, accessible, reliable, trusted and reproducible science. This is achieved largely by sharing the processes of research and data collection, and often the data, to make research results accessible, standardized, and reusable for everyone – and of course reproducible. Here we are discussing the scientific disseminated by official public health reporting agencies.

The Federal government outlines Canada’s commitment to open science with Canada’s 2018-2020 National Action Plan on Open Government, Roadmap for Open Science, Directive on Open Government, and the Model Policy on Scientific Integrity.

Our assessment will consider how well these commitments are reflected in the COVID-19 data shared by federal and provincial public health sources. We are looking for consistent adherence to open government/open data commitments.

Open Data Charter

The Open Data Charter (ODC) principles were jointly established by governments, civil society, and experts around the world to develop a globally agreed-upon set of standards for publishing data. The ODC principles include:

- open by default

- timely and comprehensive

- accessible and usable

- comparable and interoperable

- for improved governance & citizen engagement

- for inclusive development and innovation

Here, we are primarily looking for data to be open by default (1) and accessible and usable (3). This is in line with the commitment by the Government of Canada to the application of open by default specifications whenever possible; namely that data should be open-by-default and free of charge.

FAIR principles

FAIR principles are a standards approach which support the application of open science by making data Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable. The goal of the FAIR principles is to maximize the scientific value of research outputs (Wilkinson et al., 2016).

For the purposes of our current analysis we are focused on the reusability of the data available from Canada’s official COVID-19 reporting sites. As per the RDA standards, reusable data should “have clear usage licenses and provide accurate information on provenance”. Thus, we are looking for Canada’s official COVID-19 data to provide clear usage licenses which allow unrestricted reuse for all.

CARE & OCAP Principles

While the FAIR principles specify guidelines for general data sharing practices, they do not address specific issues of colonial power dynamics and the Indigenous right to data governance. The CARE principles of Indigenous Data Governance do by extending the FAIR principles. The principles are:

- collective benefit,

- authority to control,

- responsibility, and

- ethics.

Together these principles suggest that the best Indigenous data practices should be grounded in Indigenous worldviews and recognize the power of data to advance Indigenous rights and interests, and that these interests will be specific to each community but are general enough to be universal.

Similarly, the OCAP principles are a set of standards that govern best practices for Indigenous data collection, protection, use, and sharing. Developed by the First Nations Information Governance Centre, the OCAP principles assert the right of Indigenous people to exercise Ownership, Control, Access, and Possession of their own data. Taken together, these principles help maximize benefit to the community and minimize harm.

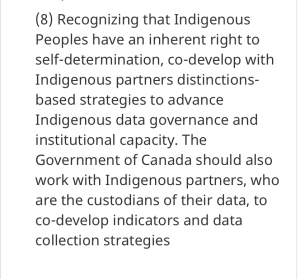

Though the federal government does not mandate adherence to CARE or OCAP principles, Canada has some commitment to fostering Indigenous data governance. Therefore we are hoping that federal and provincial institutions that produce and share data encourage Indigenous self-governance and collaboration in data collection and handling strategies.

Findings

Each of the existing open data sites were searched on Oct. 9 to assess if they disseminate COVID-19 data. Detailed results, along with a list of official COVID-19 provincial, territorial, and federal websites (including links to their data and information copyright, terms of use and disclaimers) can be found in our Official COVID-19 websites post. Links to the respective open government and open data initiatives – including policies, directives, and open data licences – can also be found there.

We made four main observations, which will be interpreted in the next section:

- All provincial and territorial, as well as the federal governments publicly publish up to date COVID-19 data.

- None of the official public provincial, territorial, or federal governments’ health sites publish COVID-19 data under an open data licence. Each claims copyright with the exception of Nunavut, which has no statements. None are open by default.

- ALL BUT Saskatchewan, Nunavut and the Northwest Territories HAVE open government and open data initiatives. Manitoba has an open government initiative but not with an open data licence.

- ONLY British Columbia and Ontario, as well as the Federal Government include COVID-19 data in their open Data Portals / Catalogues. Quebec republishes 4 COVID-19 related datasets submitted by the cities of Montreal and Sherbrooke, Ontario has 7 open COVID-19 datasets (an additional 22 supporting datasets in the COVID-19 group on the catalogue. We have not counted those in the BC portal.

Discussion

The following discusses our findings by returning to the research questions stated above:

Are COVID-19 data open in Canada?

In Canada, a work is protected by copyright when it is created and all data produced by the Federal Government falls under crown copyright; this is also the case for provincial and territorial governments (Government of Canada, 2020). Data created by these governments are considered to be open data if they are published with an open data or open government license. Under an open license the user is free “to copy, modify, publish, translate, adapt, distribute or otherwise use the Information in any medium, mode or format for any lawful purpose” (Government of Canada, 2020). Data disseminated without an open licence are governed by Crown Copyright or other types of copyright as listed here, which has specific conditions and limitations under which the information can be used, modified, published, or distributed.

With this in mind, it appears that none of the official public provincial and territorial, as well as the federal governments health sites publish COVID-19 data under an open data licence, even though the data are often accessible, public, machine readable and can be downloaded.

All of the provinces and territories – with the exception of Northwest Territories, Saskatchewan, and Nunavut – have open data portals although Manitoba has an open government portal, there is no open data license.

Where there are open data portals, only British Columbia, Ontario, and the Federal Government re-publish and disseminate the COVID-19 data via these portals (see images below). Quebec republishes 4 COVID-19 related datasets submitted by the cities of Montreal and Sherbrooke, Ontario has 7 open COVID-19 datasets (an additional 22 supporting datasets in the COVID-19 group on the catalogue. We have not counted those in the BC portal.

The Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) dashboard and website with COVID-19 data are not published under an open licence and would therefore fall under the Copyright Act – which is not open.

A screenshot of the British Columbia open data portal which republishes COVID-19 data. (Government of British Columbia, Data Catalogue). Captured October 12th, 2020.

A screenshot of the Ontario open data catalogue which republishes COVID-19 data. (Government of Ontario, Data Catalogue). Captured October 12th, 2020.

Under what licenses are the data made available?

All of the reporting sites analyzed above (with two possible exceptions, stated below) are subject to Crown Copyright, which means that a user must obtain permission from the copyright holder (the Crown) to adapt, revise, reproduce, or translate the data made available on its website.

Therefore users should assume that COVID-19 data published by all provinces and territories are protected by Copyright. All provinces and territories, with the exception of Nunavut and Saskatchewan, explicitly state their Crown Copyright protection.

Are there active open data initiatives at all levels of government? (Federal, Provincial, Territorial)

All provinces and territories – with the exception of Saskatchewan, Northwest Territories, and Nunavut – have open data and/or open government initiatives. Alberta, British Columbia, Manitoba, New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, Ontario, PEI, and Quebec have open data portals. As mentioned previously, Manitoba has an open government and open data portal, but no open data license.

Alberta, Northwest Territories, Nova Scotia, Ontario, PEI and Quebec, governments have active open data policies. All provincial and territorial governments (with the exception of Northwest Territories, Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Nunavut) make their open data available under an open government license.

At the federal level, the Government of Canada has an Open Data portal and adheres to an open government license andsome COVID-19 data are re-disseminated.

In conclusion, there are various active open data initiatives across Canada, however, they are in different stages of development across provinces and territories.

Final Remarks & Recommendations

Final Remarks

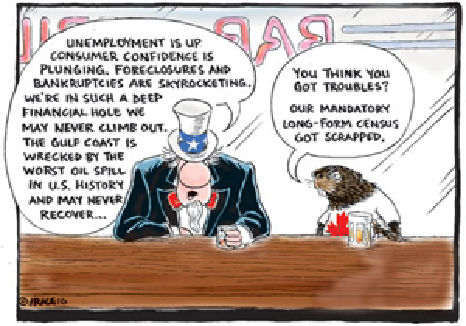

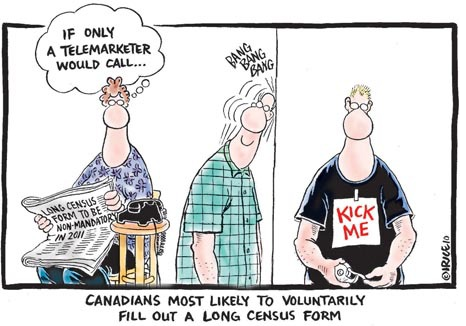

Open science, open government, and open data are initiatives increasingly adopted by the Government of Canada, but not necessarily evenly across all departments and agencies. For this reason we decided to look at the COVID-19 reporting agencies at provincial, territorial, and federal levels to determine where initiatives of openness are being adopted and where there could be improvement during the pandemic. We found that in most cases the licensing information is easy to locate, though not reflective of open data standards and licensing. COVID-19 data publicly disseminated by the official reporting agencies discussed here are not open by default or considered adequately reusable according to FAIR principles (and “reusable” standards). COVID-19 data dissemination in Canada, at the time of analysis, is incongruous with Canada’s Open Science directives.

We did not address OCAP or CARE principles in this analysis because the data we analyzed do not include categorizations of Aboriginal identity, race or ethnicity, so none of the public health reporting sites display data explicitly about Indigenous peoples. This precludes our ability to assess the collection and handling of data about Indigenous or created by Indigenous peoples, or to analyze if CARE and OCAP principles were followed. That said, there are likely other sources of Indigenous data that were not assessed here.

Recommendations

Based on these findings we have developed four primary recommendations:

- Provincial and territorial public health reporting agencies can adopt open science initiatives in their respective jurisdictions. This can be done by adopting and/or modifying the open government and open science standards which are applicable to the federal government.

- Many of the provinces and territories publish their data and information on their official websites under Crown Copyright, including COVID-19 data even when several of these institutions also have Open Data portals and/or programs. The COVID-19 data should also be re-disseminated via provincial/federal/territorial government’s open data portals to maximize the benefit of the data for scientific innovation.

- More broadly, COVID-19 data (at every level of government) should be open by default and made reusable under open data licensing. This information should be clearly indicated so that it is clear who can use the data and under what conditions. Doing so may also facilitate greater accessibility, transparency, and reuse of the data.

- Finally, there are some interoperability issues which makes it difficult for the user to ascertain whether or not the data are reusable. Each public health organization seems to have different terms of use associated with their data, and tracking down the information across websites is difficult. Further action to ensure interoperability among partners and platforms would help support the adoption of open science standards at all levels of government. This is something we will look at in a future post when we assess the interoperability of Canada’s official COVID-19 reporting sites and data.

Comments on Posts