Matthew is a graduate student at the University of Alberta, an Open Data advocate and an aspiring neogeographer. He can be reached via email at mdance@ualberta.ca or @mattdance. I met at the Cybera Data for All Summit in Banff last year.

*********************************

The GeoWeb, Citizen Science and Open Data

We are at a confluence. The two related but separate domains of the GeoWeb and Citizen Science are on a collision course with the open data and open government movement. Lets start with some definitions:

- The GeoWeb, (from Wikipedia) derived as a mash-up from geographic + World Wide Web, creates greater utility of the abstract information made available on the Internet by providing a geographic or location context. For instance, emitter.ca created greater utility of Environment Canada’s National Pollution Release Inventory by (1) making those data available as a CSV (rather that MS Access) in an open data catalogue (datadotgc.ca), and by (2) mashing the data with a Bing! Map such that the data are searchable by location – by street address or city.

- Citizen Science can be defined as scientific activities in which non-professional scientists volunteer to participate in data collection, analysis and dissemination of a scientific project (from Muki Haklay’s blog). While there are new undertones to this definition, citizen science is an old practice in Canada for the collection of climate and animal data.

To understand this collision course, it is worthwhile to understand the roles that citizens have played in GIS as a precursor to the GeoWeb, as well as with the GeoWeb itself.

The domain of Public Participation GIS (PPGIS) emerged in the 1990s with the widespread adoption of desktop computer systems that lowered barriers through reduced costs and training requirements (Longley, 2011); reduced barriers opened GIS up to more varied practitioners (Sieber, 2006). PPGIS defines a practice where GIS technology and methods are used in support of public participation and decision making in a number of domain applications (Sieber, 2000) ranging from urban planning to public policy development. The explicit desire of PPGIS is the empowerment of less privileged groups (relative to the authority implementing the PPGIS) by including them in an authority led decision processes by improving transparency and access to the input stages of a policy, or similar processes (Schroeder, 1996).

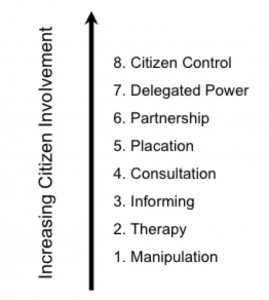

This desire for the empowerment of less privileged groups, coupled with 1990’s desk-top computer technology, defines the PPGIS process as a top down process where a central authority (i.e. government, researcher) identifies a problem, the best way to address the problem, and who can be granted access to the process to achieve the desired outcomes (Carver et. al. 2001). As such, PPGIS is a multi-dimensional entity whose core components include notions of ‘public’ and ‘participation’, but are poorly defined in the literature. In fact, it is a 1960’s model of Citizen Involvement. The following is Arnstein’s (1969) Ladder of Citizen Control most often used in the PPGIS literature.

It is the notion of Social Computing that sets the GeoWeb and Citizen Science on a collision course. Social Computing exists in contrast to the closed networks of the PC era, and can be defined as the ability of users to create, interact with and manage an information space that is dynamic, socially collaborative, portable and location sensitive (Parameswaran and Whinston, 2007). Social Computing is the technology that allows us to connect everything to everything (Hudson-Smith, et. al., 2009) in a network whose value increases as its membership increases (Benkler, 2002). As more members and devises connected to the network, the larger the information circle any one individual has. This, coupled with enhanced communication predicated on mobile devises that can record and transmit spatially and socially relevant data, potentially challenges established power structures and traditional modes of citizen engagement with an authority driven process, such as PPGIS.

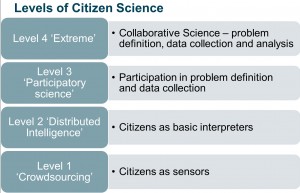

Social Computing facilitates a collision between the GeoWeb and Citizen Science by enabling citizens to participate more fully in the scientific process. Muki Haklay, proposed the levels of Citizen Science found in the Figure below. In this model Level One defines the citizen as a purveyor of volunteered geographic information (VGI) where the citizen provide observations or sensor data to a scientific process.

Level Two sees a citizen or a group of citizens act as interpreters of the data; in Level Three a citizen participates with a scientist in the problem definition and defining the data collection plan, and finally; Level Four sees the citizen working in collaboration with the scientist, even parallel to the scientist, where the citizen decides on the problems and methods to achieve a desired outcome.

Integral to this process is the fate of the data that citizen scientists provide to a process. My next post in this series will develop these ideas further and provide some examples of Citizen Science in action, including an air quality monitoring pilot project in development in Edmonton.

References:

Arnstein, S. R., A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35(4):216– 224, 1969.

Benkler Y. Coase’s penguin, or, linux and the nature of the firm. 2002.

Carver, S., Evans, A., Kingston R., and Turton, I.. Public participation, gis, and cyberdemocracy: evaluating on-line spatial decision support systems. Environ. Plann. B, 28(6):907–921, Jan 2001.

Hudson-Smith, A., Crooks A., Gibin M., Milton R., and Batty M. Neogeography and web 2.0: concepts, tools and applications. Journal of Location Based Services, 3(2):118–145, Jun 2009.

Longley, P. Geographic Information Systems and Science. Wiley, 3rd edition, 2011.

Parameswaran, M. and Whinston, A. B. Social computing: An overview. Communications of the Asso- ciation for Information Systems, pages 762–780, 2007.

Schroeder, P. Criteria for the design of a gis/2., 1996.

Sieber, R. GIS implementation in grassroots organizations. Urban and Information Systems Association Journal, 12(1):15–29, 2000.

Sieber, R. Public participation geographic information systems: A literature review and framework. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 96(3):491–507, 2006.

Comments on Posts